[ A Z A R · E T H I C S ]

“Adornments serve a particular purpose across different cultures as social markers. They are used to ascertain where one belongs in regards to identity, history and geographical location. They reveal personal information about age, gender and social class, as some beads were meant to be worn by the royalty. Beadwork creates a sense of belonging, cultural identity and tradition. Xhosa people believe that the beads also create a link between the living and their ancestors, which is particularly powerful during rituals. Therefore beads, beyond having an aesthetic purpose, also convey an important spiritual significance.”

Van Wyk, G. (2003) - Illuminated signs: style and meaning in the beadwork of the Xhosa- and Zulu- speaking peoples - African Arts, 36 (3) 12-94 [ Via the_urbanhistorian ]

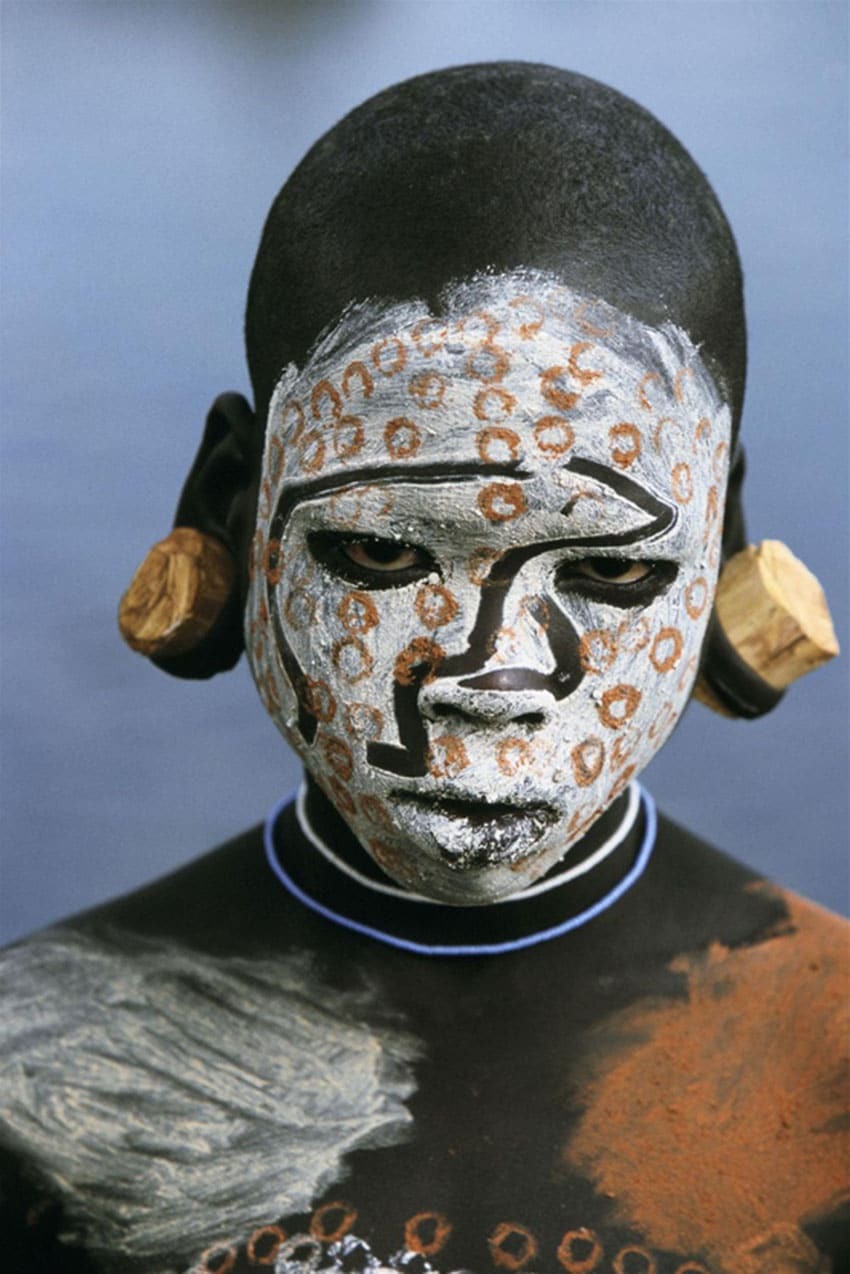

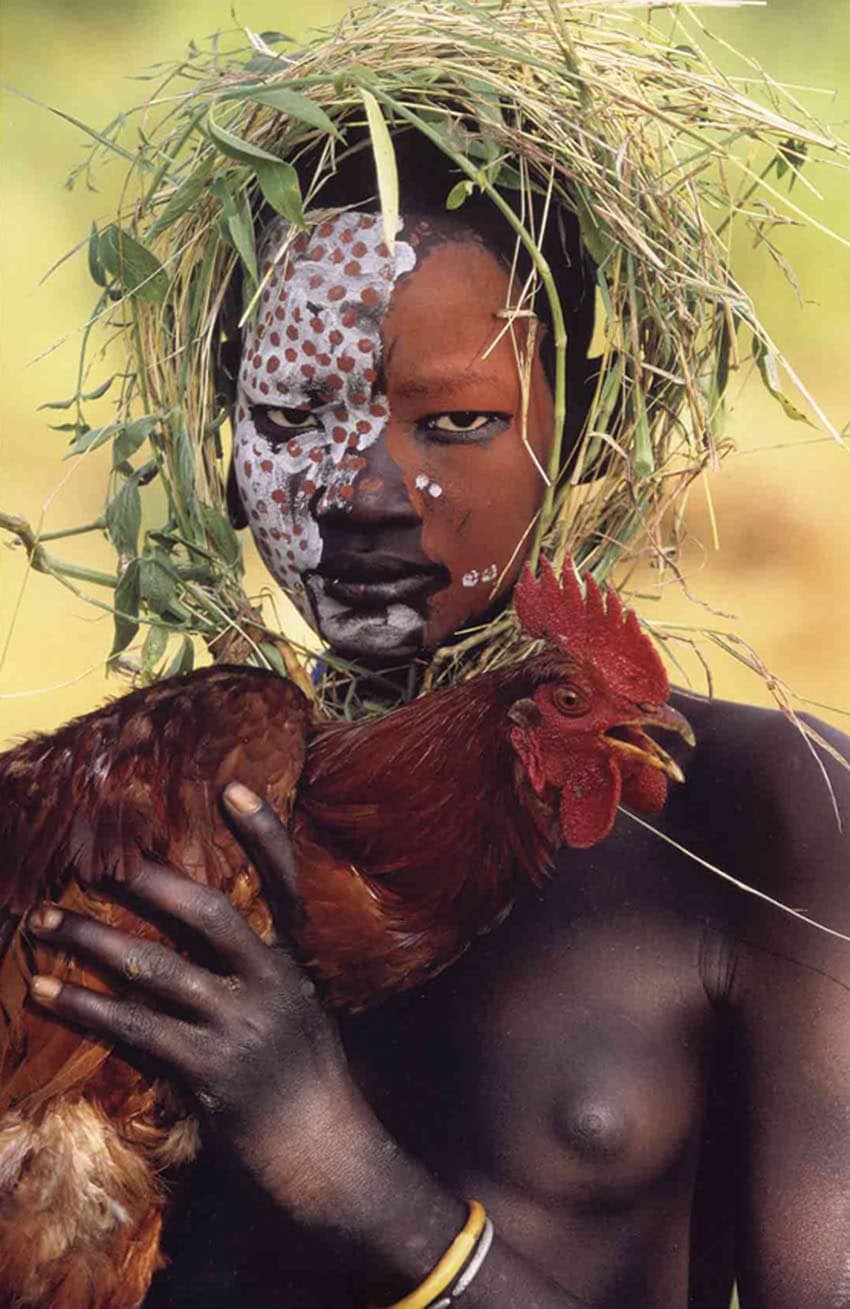

Photos taken from the book: “Ethiopia: Peoples of the Omo Valley”, by Hans Silvester

How far does this assertion lie from the current perception and use of body adornments today, in Occidental traditions and developed capitalist societies?

Our bodies, these sacred units that connect the deepest inner impulses of our interiority with the macro pulse of our social collective life on Earth, walk through our urban landscapes as “anonymous” figures, unable to convey meaning. The trend turmoil offered by the fashion industry appears to find no obstacle in us. We let ourselves be connoted by it, signified by it and homogenised by it. Season after season. As a result, our natural way of dressing and adorning our bodies consists in a passive and void attitude, depleted of any message or significance.

Nevertheless, the body, as gender studies has taught us, is not a construct of nature. It can only get known and understood from the way it is represented. It does not exist in a “normal” or “natural” way; quite the opposite: it is a constantly changing reality, from one society to the other, and even from one individual to its contemporaries. The images that define it and grant its substance, the systems that seek to know it and discover its nature, the rites and signs that foster its social mise-en-scène, vary extraordinarily from one culture to another, and constitute the core of a psychologically healthy and satisfactory social life.

Our bodies, these sacred units that connect the deepest inner impulses of our interiority with the macro pulse of our social collective life on Earth, walk through our urban landscapes as “anonymous” figures, unable to convey meaning. The trend turmoil offered by the fashion industry appears to find no obstacle in us. We let ourselves be connoted by it, signified by it and homogenised by it. Season after season. As a result, our natural way of dressing and adorning our bodies consists in a passive and void attitude, depleted of any message or significance.

Nevertheless, the body, as gender studies has taught us, is not a construct of nature. It can only get known and understood from the way it is represented. It does not exist in a “normal” or “natural” way; quite the opposite: it is a constantly changing reality, from one society to the other, and even from one individual to its contemporaries. The images that define it and grant its substance, the systems that seek to know it and discover its nature, the rites and signs that foster its social mise-en-scène, vary extraordinarily from one culture to another, and constitute the core of a psychologically healthy and satisfactory social life.

For traditional societies, the body is the element that connects oneself to collective and earthy energies, while the so-called “modern” societies imagine it as an individual structure, precisely the one that sets the limit between the individual and the social order. It is there where the body becomes the center of subjectivity, the border that keeps the individual apart from the rest of the world. In both cases, as a symbolic construction, it is a fiction that plays constantly inside a sense-driven discourse. Being the immediate support for values and aspirations, both individual and collective, it becomes a metaphor of the social body, while at the same time, the social metaphorically represents the body. As sociologist and anthropologist David Le Bretón states:

“It is impossible to correctly read the rituals that head count to any bodily expression of a society, (…) if we ignore that the body is a symbol of that society and that it reproduces, on a lower scale, the powers and dangers attributed to the social structure.”

Making ourselves conscious of this would turn our bodies into living white pages, ready to be written, represented and connoted. And dressed, which is probably the pivotal point of our thought, given that we are the ones that design and craft all the jewellery pieces and leather accessories inside Azar Studio.

“It is impossible to correctly read the rituals that head count to any bodily expression of a society, (…) if we ignore that the body is a symbol of that society and that it reproduces, on a lower scale, the powers and dangers attributed to the social structure.”

Making ourselves conscious of this would turn our bodies into living white pages, ready to be written, represented and connoted. And dressed, which is probably the pivotal point of our thought, given that we are the ones that design and craft all the jewellery pieces and leather accessories inside Azar Studio.

Photos taken from the book: “Ethiopia: Peoples of the Omo Valley”, by Hans Silvester

Photos taken from the book: “Ethiopia: Peoples of the Omo Valley”, by Hans Silvester

Through the act of getting dressed and bejewelled, the body potentially shifts from the status of instinctual, rough canvas of nature, to that of a consciously chosen reality, a means to express a subjective choice. Suddenly, it becomes a desired and wanted expression of ourselves. Garments, jewels and all forms of adornment slowly insert themselves in this subtle, daily process of “body-writing”. This sort of accumulation of conscious signs on our bodies takes a sense on its own, aside from practical, functional or even aesthetic reasons. In the deep conviction that human beings, as naturally linguistic beings, can, through dress and accessories, transform the body into a performing reality, capable of taking life and raising its voice in history.

This conclusion openly clashes, of course, with the consumerism market in perennial need of expansion; new fresh fleeting trends are to be sold, new potential best-sellers to be boosted into huge mass-productions, which are to be converted into huge gains and with this system’s fundamental need of unconsciousness from our side, both as consumers and as designers.

This conclusion openly clashes, of course, with the consumerism market in perennial need of expansion; new fresh fleeting trends are to be sold, new potential best-sellers to be boosted into huge mass-productions, which are to be converted into huge gains and with this system’s fundamental need of unconsciousness from our side, both as consumers and as designers.

Clearly as designers, crafters and entrepreneurs involved in the fashion industry, we occupy a central role. Not only by choosing noble and durable materials for our products, but also and foremost, being overly responsible of the production process: choosing to produce less, by safe means and environments, and consequently earn less. This looks to be a contradiction for a business. And it is, when the business primarily and solely aims to earn money. But is absolutely not contradictory for all those creatives who seek something more than money in what they do. It is not contradictory for the designers who struggle to create new products coming from a personal inner creative research instead of copying and reproducing what big brands dictate. And of course, it is not contradictory for those who spend hours crafting one single piece until it is perfect.

Photos taken from the book: “Ethiopia: Peoples of the Omo Valley”, by Hans Silvester

Photos taken from the book: “Ethiopia: Peoples of the Omo Valley”, by Hans Silvester

Then comes the other side, the consumers we all are, living in the apogee of consumer society. We are often depicted as helpless victims of the industry, which we are not. We have an important weapon in our hands, in every moment: we choose whom we give our money to. We choose what kind of business to support, but not only that, we also choose how to ornament our bodies. We can either follow what the majority buys and wears, mingling with masses of amorphous impersonality, wearing symbols that are not ours, that signify nothing to us, that have no value beyond its ephemeral materiality. Or we choose to live in our bodies, expressing our own beliefs and rituals, our inner voice and personal stories, in full awareness of the symbology of everything that adorns us.

Photos taken from the book: “Ethiopia: Peoples of the Omo Valley”, by Hans Silvester

Photos taken from the book: “Ethiopia: Peoples of the Omo Valley”, by Hans Silvester[ TAKE ME BACK ]

[ HOME ]